Did The Ancient Greeks Use Conscription Military Service?

Past Dr. Kevin Linch / 01.30.2012

Associate Professor of Mod History

University of Leeds

Introduction

Throughout European history monarchs, states, and governments have claimed the right to select men and force them to serve in the military. Modern conscription, whereby all the young men (and later sometimes also women) under the jurisdiction of a state were liable for armed services service and a pick of them was taken into the war machine each year, emerged in French republic in 1798 with the "loi Jourdan" during the French Revolutionary Wars (1792–1801). This commodity explores the ideas near conscription, and their communication and introduction beyond Europe during and after the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), likewise as discussing its history afterwards.

Antecedents to Conscription

Compulsory military service was not a new feature of political and social life inEurope earlier conscription was introduced during theFrench Revolutionary Wars. Across Europe there existed a variety of mechanisms by which some states could enforce service in the military. Many of these stemmed from requirements for communities or families to provide men to serve in a levy under local magnates. 1 During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries these obligations fell into disuse as armed forces forces developed into a permanent institution (oft termed continuing army) paid for and organised by the land. As such, a levy that could only be mobilised for a few months a yr became outdated. two

In response to the burgeoning manpower demands of war during the late seventeenth and the eighteenth century, specially the various wars of the 1670s and 1720s and the Seven Years' War, some states reformed systems of compulsory military service or introduced new means to supply or supplement their armies. For example, inFrance andEngland this took the course of a militia: an auxiliary, locally raised strength that was only liable to serve permanently during wartime merely undertook annual training in peacetime.

Sweden developed a special kind of allotment organization (indelningsverket), which placed the onus for manning the royal army on groups of farmers renting crown lands with units allotted to geographical areas. The new system led to a college degree of organisation and allowed for a much quicker mobilization of soldiers. The allotment system was only abolished at the beginning of the 20th century. / C.M. Gillberg later on Laurens, Soldiers of the Purple Swedish Artillery, hand-coloured engraving, Anne Due south.K. Brown War machine Collection, Brown University Library

One of the more unusual of these developments was theSwedishindelningsverket(allotment system), which was reformed byCharles XI (1655–1697) in 1682. In this, communities were obliged to provide and, crucially, maintain men and horses for the army (coastal communities provided men for the navy), with units allotted to geographical areas. As such the system was territorial as it closely linked military organisations with particular places and social structures. Another later development that was viewed with interest across Europe, and was more than widely adopted, was thePrussianKanton system. Similar theindelningsverket, this territorialised the Prussian army, assigning districts to item military units, and information technology allowed for a large function of the army to be demobilised in peacetime. 3

Every bit ways of arming the populace, all the compulsory armed services systems in Europe had limitations. A similarity betwixt these measures was their inconsistent awarding, as there were numerous exemptions from service, such as belonging to a sure social grade or territory (for example, in theUnited kingdom,Scotland andIreland had no militia, and theTyrol was not subject field to the aforementioned military code as other parts of theHabsburg Empire). Moreover, many states were wary of mass arming. In the polyglotRussian and Habsburg empires, any kind of militia would have been difficult to enforce considering they were patchwork states with multiple jurisdictions. Throughout Europe, military service was tied to monarchs and existing power structures.

Essai générale de tactique, 1772, BnF Gallica

After the Seven Years' War and theAmerican State of war of Independence, armed services thinkers beyond Europe began to seek explanations for success and failure in these wars. As part of this "military enlightenment" writers discussed the military machine and specially its relationship with society and culture. Mayhap the most famous of these wasJacques-Antoine-Hippolyte, Comte de Guibert's (1743–1790)Essai général de tactique published in 1772. In this Guibert envisaged a new manner of war that harnessed the armed forces might of the people:

Mais, supposons qu'il south'élevât en Europe united nations peuple vigoureux, de génie de moyens, & de gouvernement; un peuple qui joignît à des vertus austères, & à une milice nationnale, un programme fixe d'aggrandissement, qui ne perdît pas de vue ce systême, qui sachant faire la guerre à peu de frais, & subsister par ses victoires, ne fût pas réduit à poser les armes, par des calculs de finance. On verroit ce peuple subjuguer ses voisins, & renverser nos foibles constitutions, comme l'aquilon plie de frêles rofeaux. … Entre ces peuples, dont la foiblesse éternise les querelles, il se peut cependant qu'un jour il y ait des guerres plus décisives, & qui ébranlent les Empires. four

Nor was this a purely abstract discussion, as the late eighteenth century witnessed several conflicts that aroused the involvement of military minds and indicated a new relationship between club and war. There were several "national" wars of resistance, such equally those of the American colonists, of theCorsicans, and of theDutch in 1787–1788. Although scholarship has challenged the extent to which these were precursors to citizen armies, they were ofttimes interpreted as such by contemporaries. v

This military examination was quite open, and in that location was a general exchange of ideas through the communication channels of theenlightenment. Guibert, although French and a potential enemy, was on adept terms withFrederick Ii of Prussia (1712–1786) and discussed the Prussian military system with him. Additionally, alliances and personal ties also facilitated the substitution of ideas, such the visit of the British PrinceFrederick Augustus, Duke of York and Albany (1763–1827) to Prussia to watch military machine manoeuvres in the 1780s, and his eventualmarriage to PrincessFrederica Charlotte of Prussia (1767–1820). 6

The Introduction of Conscription

The discussion of a new war machine culture during the 1770s and 1780s was given the opportunity to be put into practise during theFrench Revolution. When war bankrupt out in 1792, the tenor of French discourse about the war was different from previous conflicts. Every bit the Revolution became threatened past the advancing Austrian and Prussian armies, and with discontent and rebellion beyond France, the Revolutionary government began mobilising France for war on a much larger scale than ever before. This resulted in thelevée en masse, which set the basic principle for conscription for the future: all the population of a polity was at the command of the state during wartime. 7

Notwithstanding, it was some time until this mobilisation was transformed into a formal system of conscription. In office, this was due to the dissonance between the rhetoric of the revolutionary government and the reality of its application: thelevée en masse expected everyone to be willing and enthusiastic about the war but in truth information technology took a expert deal of coercion to get what was needed. This resulted in France amassing a huge army – some 750,000 men in 1794 – merely information technology was a force that had no means to maintain itself at that size. 8 It was non until the political state of affairs in France became more settled nether the Directory and with peace incontinental Europe that a more permanent means to supply men for the regular army was discussed. The outcome was the 1798loi Jourdan (Law of 19 Fructidor Yr VI).

Theloi Jourdan ready the pattern for conscription in Europe over the next 100 years; each year young men (aged 20 to 25 in the case of theloi Jourdan) were put into groups, or classes every bit they were called, and a selection was made of those who were to serve in the regular army. During the ages set for conscription, every human would be liable for service each year. Service was for five years. ix This ways of supporting the army, and of the power of the state to decree how many men were to exist raised for the armed forces each year, underpinned the French Regular army for the next 17 years of war. 10

The Transmission of Conscription Across Europe

GerhardJohann David (from 1802) von Scharnhorst, Prussian general and military reformer, first in Hanoverian, from 1801 in Prussian service; 1807 appointed caput of the Military Reorganisation Commission by King Friedrich Wilhelm 3 (1770–1840); he was mainly responsible for the Prussian war machine reforms (abolishment of corporal penalization, 1808; introduction of universal armed forces service, 1814). / Black and white reproduction of an oil painting by Friedrich Bury (1810)

Initially, not much discover was paid to France's latest military police. Most European experience of the new intensity of warfare came from the early Revolutionary period of 1793–1795. Information technology was this period, and thelevée en masse, that was analysed and discussed to endeavor and empathise France's military success. The significance of conscription and the overhaul of the machinery of government to war machine power were less appreciated, and were harder to identify within all the changes wrought past the revolutionary governments of 1793–1799. Moreover, the means for gathering data about the French military were much more restricted. The Revolution and subsequent state of war had disrupted trans-European communication. Information about France was often received second manus via propaganda that accompanied revolutionary armies or the rhetoric of the Revolutionary deputies, which reinforced the focus on mass, patriotic mobilisation. Alternatively, intelligence was gathered via ascertainment from involvement in armed forces campaigns, which necessarily did non focus on recruitment. An example of this discussion tin can exist found in the volumes of theNeues Militärisches Journal (1797–1805) edited byGerhard Johann David Waitz von Scharnhorst (1755–1813). 11

This meant that the give-and-take of conscription across Europe was uneven. The timing and form of the introduction of conscription was affected by the availability of data and its communication. As a result, conscription was transmitted to other places in Europe in 4 ways:

- the imposition of French conscription in territories that were annexed to French republic;

- new states created past France as a issue of conquests, in which conscription was introduced as function of the establishment of these states;

- existing states that became allies of France and which were required to furnish troops equally part of their agreement, and and so introduced conscription to meet their manpower quotas;

- and other powers in Europe that adopted conscription to lucifer the scale and demands of warfare to fight against Franco-Allied armies.

Administrative divisions of the First French Empire in 1812 / From Andrein, Wikimedia Commons

In the first 2 cases, the introduction of conscription to the population of these areas was direct. Large parts of west and north-westItalia, someSwiss lands, theRhineland, The netherlands, and thenorthward German coasts all became role of the French Empire and and then liable for conscription. In these territories, French bureaucratic structures and organisation (départements), and crucially administrators, were introduced to oversee conscription. 12

This portrait of Napoleon by Jacques-Louis David portrays Napoleon as a both military machine and civil ruler. He wears his uniform as a colonel of the Foot Grenadiers of the Imperial Baby-sit while the sword on the chair alludes to Napoleon's military success. On the tabular array are placed several items that speak of his administrative achievements, most prominently the scroll with the discussion "Lawmaking" on it, referring to the groundbraking legal codifiedLawmaking civil established under Napoleon in 1804. / National Gallery of Art

Too every bit these annexed territories,Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821) besides created new states across Europe. In these French satellite kingdoms admission to data near conscription and its introduction to new territories was often as directly as in the annexed territories. In the Kingdoms of Italy,Westphalia, the Grand Duchies ofBerg andPolandconscription was established, unremarkably every bit office of wider political and social reforms. In the case of Italian republic and Westphalia, Napoleon himself wrote the decrees on conscription. Information technology was instituted in Italia in 1802 upon the formation of the Republic of Italy byFrancesco Melzi d'Eril (1753–1816), with Napoleon'due south approval, thirteen and was enshrined in the constitution of Westphalia when the state was established in 1807. xiv

The allied states that adopted conscription were prompted past French armed services demands and usually followed the French model. Ins-west Germany (Bavaria,Württemberg andBaden) conscription was as well role of wider social and political reforms overseen by their own administration. Frequently, these were implemented past ministers working in a tradition of enlightened absolutism, such asMaximilian Josef Garnerin, Count of Montgelas (1759–1838) in Bavaria. 15 Further impetus for change came with the welding of German states into the newConfederation of the Rhine in 1806, sixteen which required 63,000 men from the Confederation and ready military contingents for each land. This forced united states of the Confederation to examine, and in many cases constitute, French conscription to encounter their treaty obligations.

For the other larger powers in Europe –Kingdom of spain, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, Austria, Prussia, and Russia – the process of examining and changing recruitment into the ground forces was more complicated. In the instance of Austria, and Russia, they largely continued as they had done and did non drastically alter recruitment into the ground forces, although they expanded military participation by establishing and enlarging militias. 17 Britain, although relatively safe from invasion due to the power of the Royal Navy, introduced varying levels of compulsion for role-time auxiliary forces to be called out if an invasion occurred, culminating in the Local Militia Act (1808), which balloted men for service. 18 In those states that were much more direct threatened by the French there was more force per unit area to reform, notwithstanding this often had to exist carried out under difficult circumstances such as physical occupation by Franco-Allied armies or treaty restrictions. Equally such, the development of reception and give-and-take of ideas almost conscription were greatly shaped past local political culture and events. In Spain, the introduction of universal military service was codification in 1810 but the administration of the land had already collapsed as a outcome of French occupation, and and so implementation of the ordinance of 1810 was uneven. xix Prussia'due south army was restricted by treaty, which forced the army to prefer methods to train men so hold them in reserve, thus edifice up the potential size of the army. At the same time, internal debates within the ground forces and government focused on the balance betwixt arming the population and developing a professional ground forces for whatever future state of war. The full introduction of conscription had to wait until 1813 and the declaration of war against France, and this was undertaken in a very brusque timescale that precluded a full resolution of the result as the need to mobilise men into the war machine was the paramount concern. twenty

Conscription After the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars introduced conscription across virtually of Europe in one form or another. The Treaty ofParis in 1815 returned peace to Europe and instigated the Concert of Europe, and meant that states that had introduced conscription at present had to decide if they should continue using it. More often than not these were internal debates, which echoed national political issues, such as France's abolition of conscription as part of the restoration of the Bourbons, or military concerns such as the loyalty of conscription-based armies when called upon to suppress rebellions. 21 This was particularly the instance in the first one-half of the nineteenth century when most of the military activeness in Europe centred on armies intervening to restore club in both social and political events. 22

Peace brought about a new and contentious attribute for give-and-take: the mathematics and logistics of mobilisation. In this European debate, states first began deciding on the number of men to be conscripted each yr (if indeed they used conscription), their length of service, and then what to do with them after they had completed their time in the army. Comparisons were then made between states, and this dialogue was stimulated even further by the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871, when a longer serving army (the French) met a shorter-serving but larger army (the Prussians). Reflections on this state of war emphasized the need to summate the size of military machine available in a crisis, the number of men who could be called up, and the time it took to do this. In the years preceding the First World War this became the major pre-occupation, if not obsession, of general staffs beyond Europe. 23

The realities of total war betwixt 1914 and 1918 acquired governments to recognise that in a war of this kind there was more to mobilisation than merely the number of men in uniform. Governments needed to remainder the number of men under arms with the ability to feed and cloth them and supply them with weapons and armament. Consequently, states began transforming conscription into national service, whereby states took unprecedented command of the population they governed, a process exemplified bySoviet Russia and Great United kingdom during the Second Globe War. Like the initial institution of conscription across European states, this was often an internal procedure prompted past military necessities.

The Conscription Fence

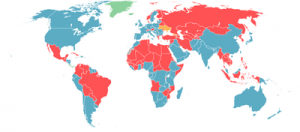

Conscription Map of the World 2011, author: Mysid, last updated: eight July 2011 / Wikimedia Commons

Within all the discussions about conscription across Europe, there take been several tensions that accept stimulated debate. Firstly, at that place has been the paradox of wanting to arm and mobilise the population equally an expression of patriotic virtue – a people'southward war – and the state imposing obligations on its subjects for military service to its own ends. 24 Secondly, conscription has occupied a central debate in the military'south function in social club, and society's function in the war machine, which ranges from a focus on a highly trained and long-serving professional army separated from gild (to the betoken of rejecting conscription) to the army serving equally a "school of the nation" where relatively short service in the armed forces served equally a means of inculcating citizenship. The latter case explains the endurance of conscription during the Common cold War and even into the early years of the 21st century. Thirdly, as technological and economic mobilisation became meaning factors in military success, compulsory armed forces service had to exist balanced confronting the economical impact of removing a proportion of the male population. Equally such, conscription has been every bit much a political, social, economic and ideological debate as it has been a military one.

Appendix

Bibliography

Anderson, Matthew Smith: War and Society in Europe of the Old Authorities: 1618–1789, Stroud 1998.

Bell, David Avrom: The Commencement Total State of war, London et al. 2007.

Blackbourn, David: History of Germany, 1780–1918: The Long Nineteenth Century, Oxford 2003.

Bond, Brian: State of war and Society in Europe, 1870–1970, New York 1983.

Broers, Michael: The Concept of "Full State of war" in the Revolutionary-Napoleonic Catamenia, in: War In History 15 (2008), pp. 247–268.

Broers, Michael: Europe under Napoleon 1799–1815, London et al. 1996.

Cookson, John E.: The British Armed Nation, 1793–1815, Oxford 1997.

Esdaile, Charles J.: Conscription in Kingdom of spain in the Napoleonic Era, in: Donald J. Stoker et al. (eds.): Conscription in the Napoleonic Era: A Revolution in War machine Affairs?, London et al. 2009, pp. 102–121.

Forrest, Alan: Conscripts and Deserters: The Army and French Society During the Revolution and Empire, Oxford 1989.

Grab, Alexander: Conscription and Desertion in Napoleonic Italy, 1802–1814, in: Donald J. Stoker et al. (eds.): Conscription in the Napoleonic Era: A Revolution in Military machine Affairs?, London et al. 2009, pp. 122–134.

Griffith, Paddy: The Art of War of Revolutionary France, 1789–1802, London 1998.

Guibert, Jacques-Antoine-Hippolyte de: Essai général de tactique, précédé d'united nations Discours sur fifty'état actuel de la politique et de la scientific discipline militaire en Europe, avec le plan d'united nations ouvrage intitulé: La French republic politique et militaire, London 1772, vol. ane–2, online: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5408326q/f6 [20/01/2012].

Hippler, Thomas: Conscription in the French Restoration: The 1818 Contend on Armed services Service, in: War In History 13 (2006), pp. 281–298.

Mikaberidze, Alexander: Conscription in Russia in the Late Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries: "for faith, Tsar and Motherland", in: Donald J. Stoker et al. (eds.): Conscription in the Napoleonic Era: A Revolution in Military Affairs?, London et al. 2009, pp. 46–65.

Nicholson, Helen J.: Medieval Warfare: Theory and Practice of War in Europe, 300–1500, Basingstoke et al. 2004.

Pavković, Michael F.: Recruitment and Conscription in the Kingdom of Westphalia: "The Palladium of Westphalian freedom", in: Donald J. Stoker et al. (eds.): Conscription in the Napoleonic Era: A Revolution in Military Affairs?, London et al. 2009, pp. 135–148.

Rothenberg, Gunther Erich: Napoleon'south Not bad Antagonist: Archduke Charles and the Austrian Army, 1792–1814, Stroud 2007.

Showalter, Dennis: Europe'due south Way of State of war, 1815–1864, in: Jeremy Black (ed.): European Warfare, 1815–2000, New York 2002, pp. 27–50.

Starkey, Armstrong: War in the Age of Enlightenment, 1700–1789, London 2003.

Stephens, H.Yard. / Kiste, John van der: Fine art. "Frederick, Prince, Knuckles of York and Albany (1763–1827)", in: H.C.G. Matthew et al. (eds.): Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford 2004, vol. 20, pp. 900–902.

Tallett, Frank et al. (eds.): European Warfare, 1350–1750, Cambridge et al. 2010.

Walter, Dierk: Coming together the French Claiming: Conscription in Prussia, 1807–1815, in: Donald J. Stoker et al. (eds.): Conscription in the Napoleonic Era: A Revolution in Military Affairs?, London et al. 2009, pp. 24–45.

White, Charles Edward: The Enlightened Soldier: Scharnhorst and the Militarische Gesellschaft, New York 1989.

Wilson, Peter H.: Social Militarisation in Eighteenth-Century Germany, in: German History 18 (2000) pp. 1–39.

Woloch, Isser: Napoleonic Conscription: State Power and Civil Club, in: By and Present 111 (1986), pp. 101–129.

Notes

- Nicholson, Medieval Warfare 2004, pp. 40–44.

- Anderson, State of war 1998, pp. 21–24; Tallett, European Warfare 2010.

- Anderson, State of war 1998, pp. 91–92, 113–114, and 120; Wilson, Social Militarisation 2000.

- Guibert, Essai général 1772, vol. 1, pp. 17–18, 22."But imagine that a vigorous people will arise in Europe that combines the virtues of austerity and a national militia with a fixed program for expansion, that it does not lose sight of this system, that, knowing how to make war at picayune expense and to alive off its victories, information technology would not exist forced to put down arms for reasons of economy. One would run across that people subjugate its neighbours, and overthrown our weak constitutions, just every bit the trigger-happy n air current bends the slender reeds. … Between these peoples, whose quarrels are perpetuated by their weakness, 1 day there might withal exist more than decisive wars, which will shake up empires.", transl. by Grand.L.

- Starkey, State of war 2003.

- Stephens / Kiste, Art. "Duke of York" 2004.

- Bong, Full War 2007; Forrest, Conscripts and Deserters 1989.

- Griffith, Art of State of war 1998, pp. eighty–82.

- Meet http://gallica.bnf.fr/Search?ArianeWireIndex=alphabetize&q=loi+jourdan&lang=EN&f_century=18&p=one&f_creator=Jourdan%2C+Jean+Baptiste+%281762-1833%29 for the reports that led to the law, and http://world wide web.napoleon.org/fr/salle_lecture/manufactures/files/conscription_le_Premier_Empire1.asp[07/06/2011].

- Woloch, Conscription 1986.

- See http://www.ub.uni-bielefeld.de/diglib/aufkl/neumiljour/neumiljour.htm [12/01/2012] for articles; White, Enlightened Soldier 1989.

- Broers, Europe 1996.

- Grab, Conscription 2009.

- Pavković, Recruitment 2009.

- Blackbourn, Germany 2003, pp. 58–59.

- The French text of the treaty is bachelor on http://www.napoleon.org/fr/salle_lecture/articles/files/traite_confederationrhin_12juillet1806.asp[07/06/2011].

- Rothenberg, Great Antagonist 2007; Mikaberidze, Conscription 2009.

- Cookson, British Armed Nation 1997.

- Esdaile, Conscription 2009.

- Walter, Conscription 2009.

- Hippler, Conscription 2006.

- Showalter, Europe's Mode 2002.

- Bond, War 1983.

- Broers, "Full War" 2008.

Editor:Peter H. Wilson

Copy Editor:Lisa Landes'

Originally published past EGO: Periodical of European History Online nether a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported license.

Comments

Did The Ancient Greeks Use Conscription Military Service?,

Source: https://brewminate.com/a-history-of-military-conscription-in-europe/

Posted by: conklingreirrom.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Did The Ancient Greeks Use Conscription Military Service?"

Post a Comment